Feature

Iain Webb’s Crystal Anniversary with the Sarasota Ballet

By Sylvia Whitman | October 2021

Fifteen seasons ago, The Sarasota Ballet and Iain Webb each took a gamble.

Founded in 1987 by former dancer Jean Weidner Goldstein, The Sarasota Ballet had grown into a respected resident company. But Goldstein and her board had bigger ambitions. In 2006, they were looking for a new director willing to make a long-term commitment and lead the organization to national recognition.

They were more than a little surprised when Webb “threw his hat into the ring,” as he puts it.

Not that Webb wasn’t worthy. He just wasn’t the conventional candidate. A dancer for 18 years, Webb retired from London’s Royal Ballet and accepted the invitation of Sir Matthew Bourne to help take Swan Lake to Broadway with an all-male ensemble. Tony Awards and world tours followed. Next, Webb commuted from England to Japan as ballet master and later assistant director of Tetsuya Kumakawa’s new K-Ballet Company. Across Europe and in the States, he produced shows, galas, and festivals. Dancers loved working with him, and more and more people murmured that he should start his own company.

With his wife, noted ballerina Margaret Barbieri, Webb hashed over the next step of his career. He realized he “always liked to be behind the scenes and fixing things rather than being out front in the spotlight.” He was in his late 40s, and Barbieri told him that if he didn’t try to be a director now, he’d be too old. So, when Webb heard The Sarasota Ballet was hiring, he applied.

Webb had never seen the company perform, and couldn’t, because it was the off season when he flew to Sarasota for an interview. He walked across the street from his hotel to the Van Wezel to get an idea of the local audience. “I didn’t watch the show,” Webb says. “It was really just watching people.” He noted a mix, some “very elegant, sophisticated people—you could feel the aura around them—” and others enjoying a rare night out. “That’s what it’s about really,” he says, “the audience coming in and forgetting what’s going on in the world outside, forgetting what their personal struggles are, and just being taken into a magical place.”

He saw promise, and The Sarasota Ballet did too. It offered him a three-year contract. Webb laughed at that notion of long-term commitment. The unwritten rule held that it takes at least five years to remold a company. But his gut said, Take it.

Plus, Webb had two secret weapons: “my address book and my wife.”

January 2007, the bet was on.

Not the Same Old, Same Old

Webb recalls an “exciting” first year, thanks in no small part to the support of major donor and board member Marvin Danto, who argued against too many artistic restrictions on the new director. Webb put together “a whole new season of follies, of choreographers that no one even heard of, like Frederick Ashton.” He chose to conclude with a “very cheeky” piece by Sir Matthew Bourne. “It just made me laugh, because it was so naughty, so on the borderline. And I felt, well, if I only last one year, at least I’ll leave with smile on my face.”

Patron Karol Fosse noticed the Webb effect right away. She was not alone: The Herald Tribune reported in October 2008 that subscriptions rose 40% in his first season.

Childhood lessons had inclined Fosse toward ballet, but she had little opportunity to feed that fondness as an adult in a Michigan town without a resident ballet company. Snowbird and later settler, she attended The Sarasota Ballet sporadically—until Webb took over. She enjoyed what has become his signature triptych, three short ballets carefully chosen to complement each other. The romantic Ashton ballets seduced her.

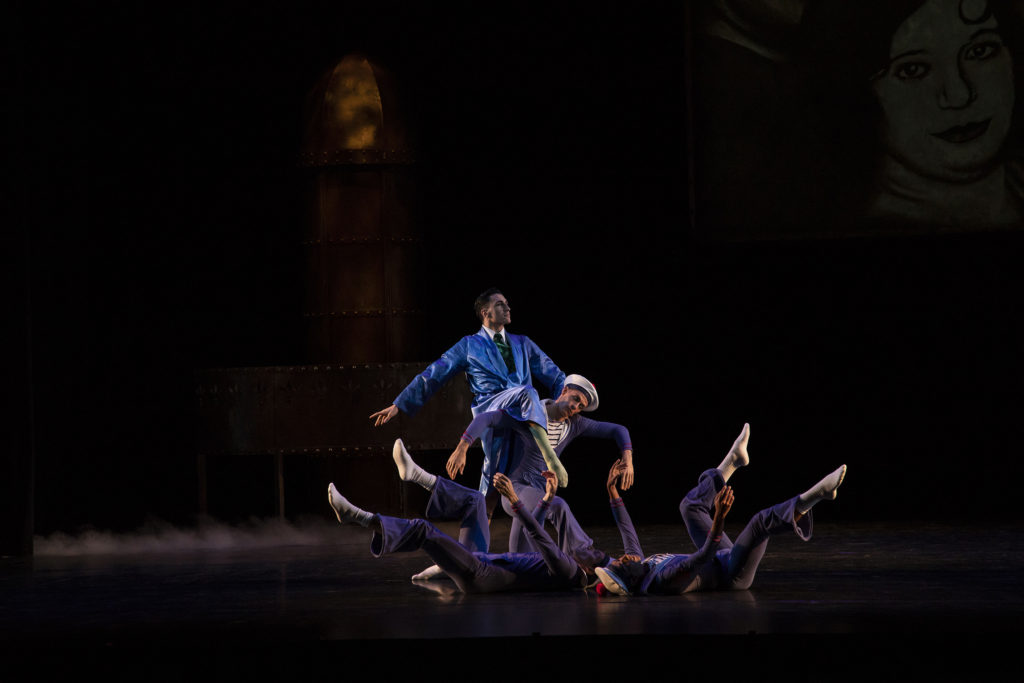

To this day, she also remembers a 2008 performance of Robert North’s Troy Game. The frills of ballet didn’t appeal to her husband, so she took her daughter that evening. “It was such an athletic ballet that both my daughter and I were almost in a state of shock. At the intermission, her comment was, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this.’ And neither had I.” They shared the same thought: This is ballet even my husband would enjoy.

Sarasota audiences rose to the challenge to try something new, again and again. According to The Sarasota Ballet’s current executive director, Joseph Volpe, Webb was able to secure permissions, attract guest artists, and deliver the highest quality collaborations because “he has a world of knowledge and connections with other dancers of other companies.” The address book. Volpe calls Webb “really wonderful” at making plans and

executing them. This, notes Volpe, who managed the Metropolitan Opera in New York for 16 years, is a rare combination with “artistic personalities.” Webb moves easily between backstage and back office.

Karol Fosse went from sporadic attender to season ticket holder. As one of the Friends of the Sarasota Ballet, she especially enjoys the monthly luncheons with glimpses behind the scenes from Webb and other company members. Webb is renowned for his deep knowledge of ballet history and his ability to give Genesis-like discourses on the genealogy of particular works.

“That kind of devotion to his work only comes because it’s really who he is,” says Fosse. “Because he’s so excited about what he does, he generates that same kind of excitement in the community. He wears his heart on his sleeve.”

A Dancer’s Director

As a new director, Webb brought Barbieri to New York with him to hold auditions. Victoria Hulland, then a trainee at the Boston Ballet School, remembers that one of her teachers insisted she go, the ballet grapevine buzzing about the prominent couple re-energizing The Sarasota Ballet.

Hulland got the offer, signed the apprentice contract, and moved to Sarasota. Where? her friends asked.

One of Hulland’s first memories of working with Iain is a funny story, she says, despite the flash of panic at the time. He asked to talk to her in his office after class. “He was like very serious music: ‘I’m so sorry, but we’ve made a big mistake with your contract.’” Hulland recalls “freaking out,” imagining herself jobless in a new town. Instead, Webb told her that the ballet should have given her a corps contract. From there, the promotions snowballed, with Hulland rising to principal in 2009.

“It’s been so cool to see the company transform over the years,” she says. The friends who first said, Where? Saratoga? Sarasota? now gush about “the rep”—the repertoire of 154 ballets and divertissements that include 39 world premieres, 7 American premieres, and the Ashton canon. “It’s not stuff that you get to see here in America a lot,” she says, “so he’s made the company really unique and special.”

Everyone notices Webb’s rapport with the dancers, how he and Barbieri—Iain and Maggie—nurture talent. (The Sarasota Ballet named coach and mentor Barbieri assistant director in 2012.) “He knows what dancers really need and what’s what, what problems they face,” Volpe says. Hulland says Webb supported her maternity leave by giving her a teaching position in the school. Through the pandemic, he helped The Sarasota Ballet figure out how to keep dancers on payroll. They know Webb has their back.

The company has risen to meet high expectations, says Hulland, because Iain and Maggie have “trusted us dancers to perform these masterpieces. Some of the roles I’ve gotten to do and ballets I’ve gotten to know I never imagined would be possible for me.” One of Hulland’s personal highlights: dancing the title role in Ashton’s Marguerite and Armand—the first performance of that ballet by an American company. “It was huge to be trusted with that,” she says.

Webb himself notes that “the dancers will do anything for me. They trust what I’m trying to do.” He loves reminding them of their place in ballet history, the lineage of a costume or a role, and giving them “gifts” usually reserved for major companies. The Sarasota Ballet also cultivates company choreographers, most notably dancer Ricardo Graziano.

Webb still teaches class. Hulland says everyone can tell when he’ll be coming to the studio because he wears his yellow-and-black-checkered sneakers. She says she’s stayed 15 years not just for the amazing roles but for the esprit de corps Webb has created, dancers helping each other out and cheering each other on. “I think he has made sure that people have acted in that way. If he has ever sensed anything otherwise, he’s made clear we’re not going have that kind of behavior here. It starts from the top.”

“When a dancer leaves us, it breaks his heart,” Fosse says. Of course, Webb helps his protégés move on to a larger company or a new venture. “But it’s like having your children, you know, getting married and move away,” Fosse says. “I don’t think he would admit to that, but that’s really who he is.”

No Longer the Underdog

The Sarasota Ballet kept renewing Webb’s contract. It didn’t take long for everyone to recognize the wager as a win-win.

“Iain will be in the office, seven days a week, doing something,” says Volpe. “He is just 100% committed to The Sarasota Ballet.”

To Webb, the commitment feels mutual. From founder Goldstein to the board to the audience to the donors, “the most amazing thing is how everybody’s opened their hearts up to The Sarasota Ballet, to the dancers and to what Margaret and Joe and I are trying to do. I still sometimes can’t believe how people have been so loving and caring about the company.”

Webb finds it hard to pick out just one highlight from his long tenure. Achieving national—and international—recognition took just a few years. In 2011, Suzanne Farrell, “Balanchine’s muse,” invited The Sarasota Ballet to partner on a production of Diamonds with her company based in Washington, D.C. Two years later, the Kennedy Center invited The Sarasota Ballet back as one of nine companies featured in Ballet Across America, alongside “big guns” like the Pennsylvania and Washington ballets.

That was an honor, but Webb says the company was “kind of an underdog,” performing an older piece by Ashton (of course), “Les Patineurs,” far less familiar to the audience than the other troupes’ programs. The Sarasota Ballet did so well, though, that “the Washington Post said we were the crown in the jewel of the festival,” Webb recalls. That prompted a New York Times reporter to travel to Florida to suss out the story behind this “miracle,” as the critics described it.

“Mr. Webb sees an analogy between his small company and Ashton’s scrappy beginnings,” the Times reporter concluded. “Perhaps someday no one will think it incongruous for [Ashton’s] ballets to have a home in Sarasota.”

That day has already come. Webb and company are looking forward to a 2021-2022 season with works by Ashton and Dame Ninette de Valois, Twila Tharp and Marc Morris, and more. Sir David Bintley is sojourning in Sarasota to produce his full-length ballet, a world premiere based on Shakespeare’s A Comedy of Errors. “It’s going to be such fun, to have somebody like him in the house, creating this work on the dancers. I’m sure the audience will find it—and everything—really amazing,” Webb says.

For more information about the upcoming season and COVID protocols for attending live performances, see The Sarasota Ballet website: www.sarasotaballet.org

You must be logged in to post a comment Login