Literature

Beach Reads: Final Masterpiece

By Elise Covino | August 2022

Paul Gauguin’s vision blurred as his horse trotted along the dirt track out of Atuona. In the midday heat, he passed a Marquesan man carving a wooden paddle, a young boy sorting dried coconut flesh, and a woman hauling crabs in a woven palm basket. Ordinarily, these South Pacific island scenes drew his eye, but on this day, the artist was too deeply shaken to notice.

Gauguin entered his seaside hamlet’s central clearing. He didn’t see Ku tending his taro garden. Or Joris picking breadfruit. Or Oliana minding her goats and pigs. His horse, familiar with its owner’s habits, slowed on its own.

Manu, grower of oranges and coconuts, approached. “Paul, you don’t look so good. What did Doc say about the sores?”

Gauguin blinked, but his eyes refused to focus.

Manu’s brown complexion paled. “Is it…the grande verole?”

At those words, Gauguin’s trance broke. “Oui. Syphilis.”

Manu winced. “I am sorry. Did he give you any remedy?”

Gauguin pulled two white envelopes from his pants pocket. “Morphine for the pain. And mercury.” He showed Manu the tablets. “Not sure which is worse, dying from the disease or the cure.”

Manu gazed at his feet. “What will you do?”

Gauguin shrugged. He had no idea and, in his current state, no desire to consider it. About one thing he was certain, though—he could postpone his decision-making by spending the afternoon in a whiskey-induced stupor.

“How can I help?” Manu asked.

“Bring some oranges.”

Manu hurried off to fetch the fruit from his small grove.

After allowing his horse to drink at the community trough, Gauguin rode to his thatch-roofed hut and tied the animal to a backyard post. Inside his one-room home, he drew back the tapa cloth curtain concealing a large window facing Ta’a ’Oa Bay. The view from this window had never failed to delight him. Verdant, jungle-covered mountain ridges embraced aquamarine waters dotted with vermillion and cadmium yellow fishing boats. Temetiu, the highest peak, rose majestically from the bay’s west end into a cobalt blue sky. Ever-present zinc white clouds tinged with gray ochre hung above. To Gauguin, this was a seascape more perfect than he could ever hope to paint.

He sat at his scarred wooden table and stared out the window, barely noticing the terns and plovers scampering over wet sand. For months he’d feared that his sores and nightly bone pain signaled a serious affliction, but he hadn’t allowed himself to imagine an imminent death. When Doc told him, mercury tablets or not, his life would likely end soon, he’d been utterly thunderstruck.

A knock shook Gauguin’s door, startling him from his daze. He stood and opened it.

Manu carried a basket of oranges and a slab of tuna wrapped in a banana leaf into the hut and deposited them on the table. “Thought you could use some solid food too.”

Gauguin nodded his thanks. He filled a hollowed-out coconut with French whiskey he’d bought with proceeds from the sale of a painting and extended it to the fruit grower.

Manu took it in both hands. “That’s way too much.”

“I won’t be needing it.”

Manu drank from the cup and set it down next to the fish. “The mercury might work.”

Gauguin scowled. “Unlikely.”

“Then here.” Manu grasped the carved bone tiki pendant resting against his tattooed chest and pulled the attached leather strap over his head. “This will protect you.” He placed the pendant on the artist’s palm and closed his fingers over it.

“If only.” Gauguin stuffed the necklace into his pants pocket.

“When are you returning to France?” Manu asked.

“I’m not.”

“Why not?” Manu frowned. “Surely you want your family close now.”

“Yes, but that’s not possible. My wife sent me away. Two of our children are dead. The other three won’t speak to me.”

“Can’t you settle your differences before . . .”

Gauguin shook his head. “Even if we did, they could never tolerate the disgrace my disease would bring them.”

Manu sipped his whiskey. “What about friends? You must have many in France who would be a comfort.”

“Friends? I have none.”

Manu looked wounded. “You have me.”

Gauguin continued as though he hadn’t heard. “Pissarro is disgusted by my work. And Van Gogh? Our friendship ended after our row and that incident with his ear. Now he is dead.”

“Then, not to worry. I will get you through this.”

Gauguin, in no mood for optimistic chatter and eager to anesthetize himself, sent Manu away. He poured whiskey to the halfway mark etched inside a coconut cup, cut an orange, and squeezed it over the cup until its juice reached the rim. Seated before his beloved view, he gulped the entire drink.

While he waited for the liquor to blunt his emotions, he examined the contours and hues of a stately heron near the water’s edge. The whiskey soon melted his muscle tension. But it did not deliver the longed-for mental escape. Instead, it aroused an intense sadness in him. He reflected on his lifetime devotion to creating art worthy of respect from the great French painters he so admired. And on how after all his years of trying he’d hadn’t achieved the fame and success he so desired. Now it was clear he never would.

Blinking away the wetness that threatened to fill his eyes, he stirred a second whiskey and orange juice with his finger. As he chugged the entire drink, his distress turned into anger. It wasn’t fair. Why should others live to realize their dreams while his life simply ended? He slammed the empty cup down on the table.

A third whiskey-and-orange awakened fears of death’s prelude. The bothersome sores would gnaw deeper. His joint and muscle pain would become excruciating. He’d be haunted by the nightmarish hallucinations of a demented mind. How was he to endure such suffering?

He swigged whiskey straight from the bottle. His wife was right. He had neglected her and the children. Even though he cared deeply for them, he’d felt compelled to spend nearly every waking hour painting. And for what? Several minor exhibits? A few meager sales? It hardly seemed worth it.

So what now? Spend his remaining time on a long, difficult journey to France to beg for forgiveness? Or stay on Hiva ’Oa and fill his last days with a final attempt to create a masterpiece fit to hang in the Louvre? He groaned. In his inebriated state, he hadn’t the strength of mind needed to arrive at an answer.

Gauguin rested his forehead on the table and listened to the waves crashing rhythmically ashore. Before long, the oblivion of sleep claimed him.

He awoke with no idea how many hours had passed. Groggy and disoriented, he blinked until his vision cleared, then looked through his window.

An obscure line split the black sea from the graphite sky. Dawn was at hand.

Soon fuchsia and violet streaked the heavens, silhouetting low-hanging clouds. The volcanic ridges lining the bay emerged from the murky haze and reached for the junction of sea and sky as if embracing the new day. A golden semicircle peeked over the horizon and grew into a glowing orb. Its glistening beacon reached toward shore, turning wave crests metallic silver.

So captivated was Gauguin that he barely noticed the searing sores on his left arm. As the morning mist cleared, so did his mind. The answer to his dilemma was obvious. He must devote his remaining time to a painting that captured the splendor of a Polynesian sunrise. It would be the culmination of his life’s work, the masterpiece he’d long yearned to create.

He set about planning it while breakfasting on coconut and mashed taro root. Watercolors dried far faster than oils and would give the work a more nebulous quality. Shades of apricot and indigo were essential. Tingling with anticipation, Gauguin assembled paints, palettes, and brushes and spent the afternoon roughly sketching Ta’a ’Oa Bay’s curves.

Following a supper of breadfruit and goat cheese, he lay on his straw tick mattress, hoping to fall into an early slumber that would assure a pre-dawn awakening. But the pain in his arms and legs, intensifying by the minute, kept him awake. He tried to lull himself to sleep by imagining the hues and shapes that would fill his canvas the next day. When that distraction proved ineffective, he swallowed a morphine tablet with a sip of whiskey. The aching in his bones softened. He fell into a slumber disturbed by dreams of lengthy, arduous sea voyages. In each, he expired before ever reaching his wife and children.

After a third nightmare woke him, he abandoned his attempts to sleep and sat at his table, waiting for the sun to transform the ebony sky. Hours later, another day was born. To Gauguin, it was even more awe inspiring than the phenomenon he’d observed the day before. Exhilarated, he traced cloud outlines on his canvas and applied slashes of orangey-pink and buttery yellow. Working quickly, he struggled to depict the spectacle before the morning light lost its softness.

The haze cleared as the gilded sphere rose. The sky’s profusion of color dissolved into a uniform cornflower-blue. Gauguin raced his fading memory to recreate the exquisite daybreak. The sun was at its pinnacle when he stood back to evaluate his work.

Something was off. In some indeterminate way, he’d failed to capture the glorious event’s magical component, its essence. Gauguin collapsed into his chair. He grabbed a clump of hair in each fist and pulled. “Argh.” This painting was not even adequate. He’d been such a fool. He’d sacrificed closeness with his loved ones to pursue an occupation at which he’d never excel.

Guzzling whiskey from the bottle, he squinted at his sunrise rendering and compared it with his mid-day view through the window. Near the shore, a fisherman was filleting tuna on a wooden plank. Gauguin ignored him and studied the dense growth covering the mountains and the curve of the bay. Had he depicted the arc of the ridges too loosely or tightly? Or did color hold the key?

A local woman named Tehani, clad only in the pareo wrapped around her waist, wove through the palms next to his hut with her twin four-year-old boys and pre-teen daughter. The family made its way onto the beach as Gauguin muttered about the correct shade to use for the silvery light reflected off the sea at sunrise. Tehani waded into the aquamarine water and stood on a sandbar, gathering clams and cowries. The little ones joined the search, and one triumphantly pulled a small conch from the water. Tehani responded with a joyful exclamation and a pat of praise to his head.

Gauguin again took in the entire scene. In a flash of inspiration, he knew what was missing. He set about correcting his mistake.

For three days he toiled at perfecting his final painting. On the afternoon of the fourth day, Manu knocked on his door and called to him. Gauguin yelled, “Come back in an hour.”

Gauguin added the finishing touches and set his brush on the table. He placed his easel at the foot of his mattress and lay down to enjoy his life’s greatest work.

That evening, after Manu finished picking oranges and trading them for his household needs, he returned and again pounded his fist against Gauguin’s door.

Gauguin moaned from his mattress.

Manu opened the door and poked his head through. “You okay?” Concern etched his face when his friend didn’t respond. He rushed to Gauguin’s bedside. “What’s wrong?”

Gauguin, his eyes half closed, pointed toward the wooden nightstand next to his mattress.

Manu followed his finger to the empty morphine tablet envelope. “No. Tell me you didn’t!”

“It’s okay. Everything is in order.” Gauguin’s gaze shifted toward the foot of his bed. “I’ve accomplished what I set out to do.”

Manu turned to see what had caught Gauguin’s attention. “Oh.”

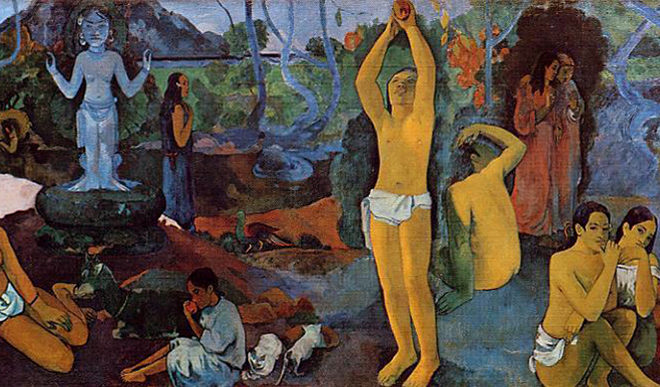

For several moments, both men silently contemplated the painting. The background consisted of the subtle colors of a Ta’a ’Oa Bay sunrise. In the foreground, a woman and five children gazed lovingly from the canvas. A tattooed Polynesian man who more than slightly resembled Manu occupied the lower left corner. In his hand was a basket of oranges. On his face was an expression that reflected his eagerness to help a friend in need.

Manu’s eyes lit up. “That’s me?”

Gauguin nodded.

“You did it,” Manu said. “You brilliantly portrayed all that is important to you. It is indeed a masterpiece.”

With sigh of contentment, Gaugin gently closed his eyes.

About the Author

Elise Covino is a University of Buffalo graduate whose long career as a paralegal in a personal injury firm ended with a switch from brief-writing to fiction-writing. Her nearly complete first novel, a mystery, is set in a fictional Florida city that may seem familiar to Sarasota residents. She resides in Bradenton.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login