People

Betty Rosen: The World Through My Eye

The Amazing Life of Photographer Betty Rosen

By Ryan G. Van Cleave | Opening Photo by Jordan Kelly-Laviolette

Betty and Buddy Rosen have been traveling the world for the better part of three decades because they wanted to “see what’s out there,” they say. More to the point, Betty wants to capture the best of it on film. “I’ll do anything to get the photo,” she promises, and Buddy jumps in, saying, “She’ll yell ‘STOP THE CAR!’ And she’ll jump out to take a shot of something I simply don’t see. It might be a view through a fence where a specific image comes out to be a face on a rock. She sees things others don’t. So we stop every time.”

Now that the Rosens have relocated to Sarasota—though they still summer back in Baltimore in a house “that’s like a museum, thanks to all the art” Buddy adds—we can catch up with Betty and find out just what it’s like to be a fine art photographer with an international reputation.

“Around 30 years ago, I started carrying a $30 Minolta 35mm with me and shooting whatever caught my eye,” she explains. In the 1970s, she wanted some feedback on her work, so she took a course at the Smithsonian. In a critique, the instructor said something about an f-stop. “What’s an f-stop?” Betty asked, to which the instructor replied, “Don’t take a photography lesson. It’ll ruin you.” And she never did.

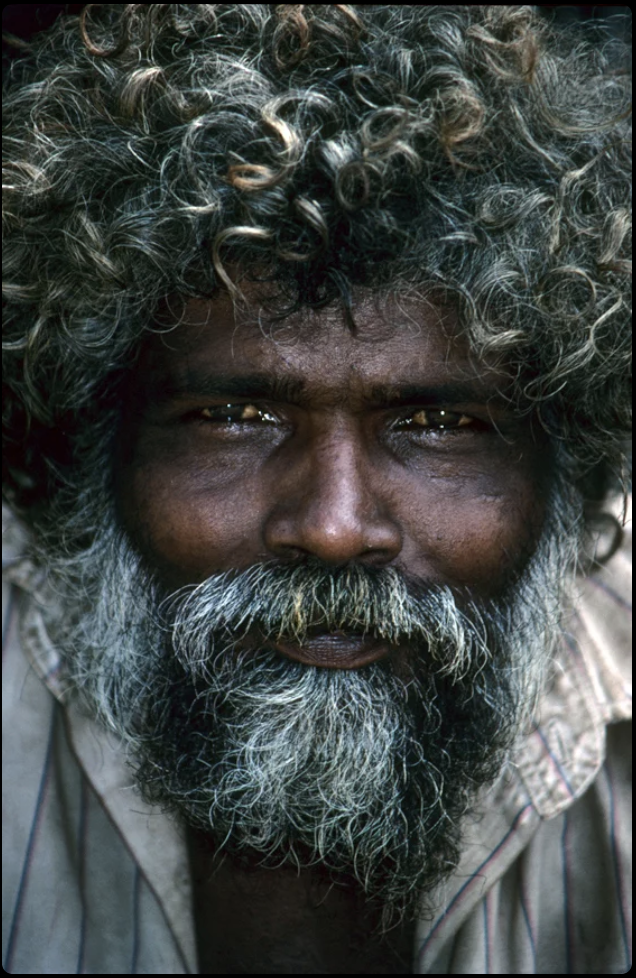

More often than not, what catches Betty’s eye are tribal people and endangered cultures from the most remote places on the globe, such as the West African Dogon tribe where masked ceremonial dancers walk on stilts. “It was 105 degrees out and we drove past in a truck,” Betty recalls, “and I kept thinking that these pictures better come out!” Or there’s the open-air laundry in Delhi, India, where men beat clothes clean with flogging stones. Or the majesty of the May Day Parade in Ulan Bator, Mongolia. Or there’s the women of Yemen, where it’s illegal to take photos of them. “But I did anyway,” she says. “I had to take the risk.”

One of Betty’s favorite locations is New Guinea, which they’ve visited many times. The first time there, the Rosens stayed a month in the same area that Nelson Rockefeller was killed—the Asmat region of southwestern New Guinea. “I was young, white, and blonde-haired,” says Betty about this 1971 trip where she and Buddy drove a Jeep over the Owen Stanley Mountains and they found themselves in a village made up of naked men. “These were the mud men of the Asaro River—one of several cannibalistic tribes in the region,” Betty explains. “They’d never seen blonde hair before and they were mesmerized. Finally, the chief decided to cut off my hair with a knife. There were 200 of them and just two of us. What could I do but agree? We spent a few hours with them before moving on.”

In another village on that same trip, she encountered a village where naked women breastfed their pigs—a baby on one side, a pig on the other. “For them, pigs are holy, like cows are in India.” The children there were different, too, in that schooling for them wasn’t about reading and writing—it was all about survival.

“We never made reservations,” Buddy explains about her lifelong passion for travel. “We just got on a plane and went somewhere. We never got stuck sleeping in a car—we always found a place to stay.” Betty adds, “Our feeling was that if you have reservations, what do you do if you want to stay somewhere for four days versus the two you originally planned?”

People often wonder if Betty’s stunning pictures are posed. “Never,” she says. “And it’s rare that I’ve been turned away.” Buddy points out that she doesn’t pay for photos either. If potential subjects ask for money, it’s a pass. But there’s something about her that’s so agreeable that it’s easy to see why most simply say yes.

One of Betty’s more recent photographic interests are transsexual exotic dancers. She first encountered them in Phuket, Thailand where close friends of hers owned a restaurant.

One night, they talked about the local transsexual shows and told her, “You’ve GOT to see them.” Before long, they were taking her out to private clubs every night after the restaurant closed, and she’d be there until 5 in the morning, snapping photos of all the ultra-feminine, bejeweled subjects. “She has this unusual ability to see what makes people special,” Buddy says. And that’s exactly what makes her photos so compelling and rich with detail.

Recently, a professional photographer came to the Rosen’s house to use some of her pictures for a project, and he said, “This stuff is great. You ought to do something with it.” To that end, she’s now working on a coffee table book. She started with 10,000 slides, though now she’s worked it down to 2,500 with the goal of only choosing 120 for the book that should be out in fall 2019. But it’s a tough task since her photos are all full of empathy, compassion, and vision—which to select? “I’ll get it done,” she promises. “Eventually.”

One thing that people immediately realize when seeing Betty’s framed photos is that they’re huge, often being 2 by 3 feet or bigger. “I don’t do anything small,” she explains, though she could just as easily be talking about her amazing life, too.

For more on Betty Rosen and her fine arts photography, visit www.bettyrosen.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login