Feature

Spotlight: Making Brain Waves

The Roskamp Institute Brings Big Science to SRQ

By Sylvia Whitman

January 2021 — Sarasota is synonymous with arts, not sciences, but a growing presence of researchers, clinicians, and entrepreneurs is expanding the regional resume. Founded in 2003, the Roskamp Institute belongs to the medical vanguard. In an unpresuming complex not far from Sarasota-Bradenton International Airport, about a dozen senior scientists are winning six-figure grants from the likes of the Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health, and Veterans Administration to tease out the mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease, Gulf War illness, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among other neurological ailments. A running tally on the institute’s website celebrates the successes of the past 17 years, including more than 450 publications.

Most brain research of this caliber takes place in the labs of large universities, but the Roskamp Institute is one of the rare stand-alone scientific organizations. (Think San Diego’s Scripps Research.) Nimble, independent, and highly productive, the nonprofit institute prioritizes “translational research,” discoveries that move quickly (by scientific pacing) from lab bench to bedside. Although Roskamp methods and findings undergo the same scrutiny as other peer-reviewed studies, the institute’s goal is knowledge aimed toward more accurate diagnoses or better care—research for treatment’s sake. The Roskamp Institute also runs a neurology clinic that often doubles as a site for clinical trials of screening tools and medications. Says president and CEO Dr. Fiona Crawford, “Everything is about the end game in the clinic.”

How a world-class research facility with about 65 staffers and a handful of PhD students bloomed in a repurposed Bausch & Lomb building on Whitfield Avenue attests to the power of curiosity, personality, philanthropy, and serendipity. In the early 1990s, Dr. Crawford and Dr. Michael Mullan, now the Roskamp Institute’s executive director, discovered the genetic underpinnings of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease as part of a European research team at London University. The breakthrough was a big deal. Published as “A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer’s disease in the APP gene at the N–terminus of β–amyloid,” the study drew attention to the accumulation of amyloid proteins in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. That suggested that if researchers could develop an amyloid-busting drug, they might open avenues for effective treatment for a progressive disease without much hope. Alzheimer’s disease afflicts more than 5 million Americans—and, along with other dementias, more than 50 million people worldwide, with a new case diagnosed about every 3 seconds. As academic celebrities, Drs. Crawford and Mullan began looking around for the best place to continue their research.

They came to the University of South Florida, in part because Sarasota philanthropists Robert and Diane Roskamp were funding new labs there. As a developer of senior living facilities, Bob Roskamp had witnessed the toll of dementia on patients and their caregivers, so he and his wife took an interest in Drs. Crawford and Mullan’s ambition to do research that promised impact on patient care. Together, the four envisioned a streamlined, state-of-the-art institute light on academic bureaucracy.

The Roskamp Foundation launched the nonprofit Roskamp Institute. In another departure from university custom, the institute set up a neurology clinic under the same roof for people suffering from memory disorders, multiple sclerosis, headaches, Parkinson’s disease, and previous brain injuries—the gamut of neurological maladies. Run by Dr. Andrew Keegan, the clinic now serves about 6,000 outpatients every year. It offers care informed by the latest research, often including opportunities to participate in clinical trials. And the clinic gives researchers access to subjects often willing to fill out questionnaires or share blood samples.

Like a university neuroscience department, the institute also trains PhD students—but European style. Doctoral candidates enroll at the Open University in the United Kingdom and carry out lab work at Roskamp Institute, accredited through the Florida Department of Education. When a Roskamp scientist needs a graduate student for a long-term project, a recruitment notice goes up. “We get applications from all around the world,” says Dr. Crawford. “It’s a pretty high bar, pretty rigorous screening process with multiple interviews,” many of them online even in pre-coronavirus days. Once accepted, PhD students move to Sarasota, combining distance and on-the-job learning for three or four years as they earn their degree. Occasionally, science-minded undergraduates—from New College, for instance—intern alongside them in the lab.

Purposeful science in “paradise” has fostered a stable workforce. A number of newly minted PhDs have graduated into full-time Scientist l, ll, or lll positions at the Roskamp Institute, resulting in a very cosmopolitan staff directory.

Projects branch out like neurons

The organization initially built upon the co-founders’ discoveries, exploring how Alzheimer’s disease impacts the brain. Their amyloid findings have led to a couple of promising potential treatments, but none has yet won approval in the United States. Roskamp research showed that Nilvadipine, a hypertension medicine used abroad, lowered levels of toxic proteins in mice brains, and clinical trials in Europe noted less cognitive decline in patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s. But disappointing results in people with later-stage disease indicated more work is needed. And the anti-amyloid antibody aducanumab seemed on track for distribution through the Roskamp Institute clinic—until an FDA advisory committee applied the brakes in November 2020.

Dr. Mullan says medication development has been “a long and rocky road. There have been many drugs aimed at amyloid, and the vast majority of them haven’t worked. We believe that’s because there are many different forms of amyloid, and you have to go after the right one.”

Nonetheless, Roskamp Institute studies have deepened understanding of the brain. In science, success and citations build credibility, and the Roskamp Institute’s track record and leadership—a sort of force multiplier—guarantee its grant applications serious consideration. Alzheimer’s research has also served as a “roadmap of all of the other programs” in the laboratories, says Dr. Crawford. Neurological distress from inflammation, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, runs through most of the organization’s research areas. So does the goal of “translatable” results that can lead to new screenings and/or treatments.

On a technique level, the institute’s long experience with Alzheimer’s disease has speeded up the research process. Investigators already know how to access to tissue from autopsies and brain banks and how to test ideas in mouse models. “At the end of the day we have to get into an organism to find out what’s going on,” Dr. Crawford says.

Dr. Benoit Mouzon, one of the early graduates of the Roskamp PhD program, developed an animal model of repetitive closed head injury to study mild traumatic brain injury (TBI)—concussions. TBI can happen to people across the lifespan, from “shaken babies” to athletes to elders who fall. Tapping samples from a city brain bank in Boston, Dr. Mouzon has compared brain tissue in football players and mice, for instance, noting that TBI results in inflammation in brains of both species. Dr. Joseph Ojo is examining widespread, persistent inflammation from TBI at the cellular level under a Department of Defense grant.

One insight leads to another

Dr. Lailah Abdullah, another Roskamp Institute graduate turned staff neuroscientist, is probing the fatigue, headaches, memory loss, and other symptoms surfacing in a number of Gulf War veterans. Inflammation again appears to be the culprit behind Gulf War Illness—the result of an overactive immune response perhaps triggered by exposure to pesticides.

Ongoing support for Roskamp Institute research now comes 95% from grants, says Dr. Mullan. Yet donations remain essential to sustain the institute and seed new projects. Young researchers don’t always get funded on their first application, and even seasoned scientists may have to revise and resubmit after critiques. “It can be 12 to 18 months before a project gets funded,” says Dr. Crawford.

She points out that philanthropic funds also enable Roskamp labs to pivot and act quickly. “If there’s something I’ve identified today as being critical, it could be 2022 before I actually get [grant] funded to work. If it’s that important, we really need to be working on it,” she says. Thanks to donor money, “whenever we make a new discovery or we identify a new direction in the lab, we can act immediately.”

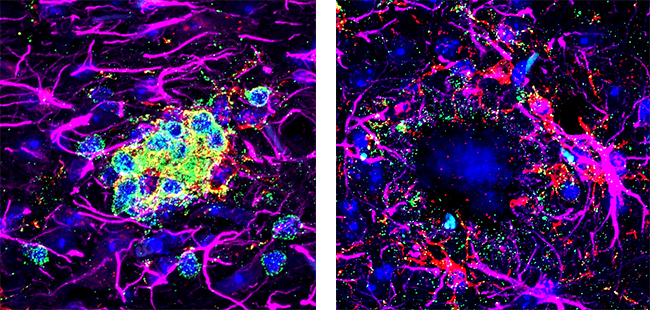

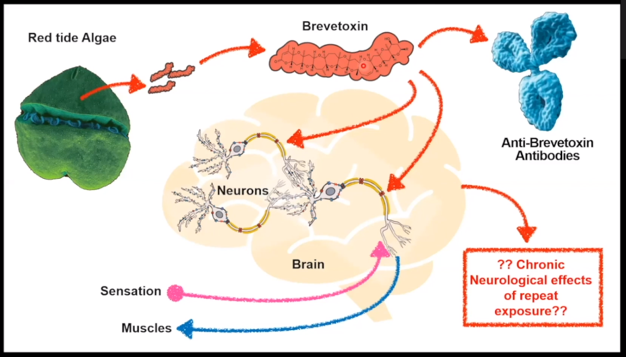

A case in point: the Red Tide Project. As seasonal Red Tide algae (Karenia brevis) surged along the Gulf Coast in 2018, killing fish and birds and sickening beachgoers, Roskamp scientists wondered how the neurotoxin (brevetoxin) released by the algae might affect the central nervous system. Dr. Abdullah took the lead; in the Gulf War Illness project, she was already sussing out the relationship between systemic symptoms and environmental exposures. Adept at measuring and quantifying inflammation, researchers began taking blood samples from coastal residents and a control group living inland. Donor funds underwrote that $40,000 pilot study, the data from which Roskamp Institute parlayed into a successful $400,000 award in May 2020 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to explore brevetoxin and brain health. Researchers plan to gather blood and urine from 400 volunteers in Sarasota and Manatee counties and measure antibodies during red tide blooms and off seasons.

Might the Roskamp Institute have something to offer in the fight against Covid-19? “We’re particularly interested in this phenomenon called long Covid or long haulers,” says Dr. Mullan. Some people infected with the coronavirus—and not necessarily the ones who have had the severest acute disease—over time develop symptoms strikingly similar to veterans’ chronic fatigue syndrome, an area where Roskamp researchers have worked for a number of years. Long haulers develop or continue symptoms months after their bout of Covid-19, complaining of “brain fog” and fatigue so extreme that they “can’t get out of bed for three days,” explains Mullan. “We’re definitely looking into that.”

If there’s a neurological entrée into the pandemic and its aftermath, count on the Roskamp Institute to ask the right questions and begin seeking answers. Art helps us cope; science help us cure. Sarasota is working on both fronts.

For more information on Roskamp Institute, visit roskampinstitute.org or call 941.752.2949.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login