People

Scenes From an Interview

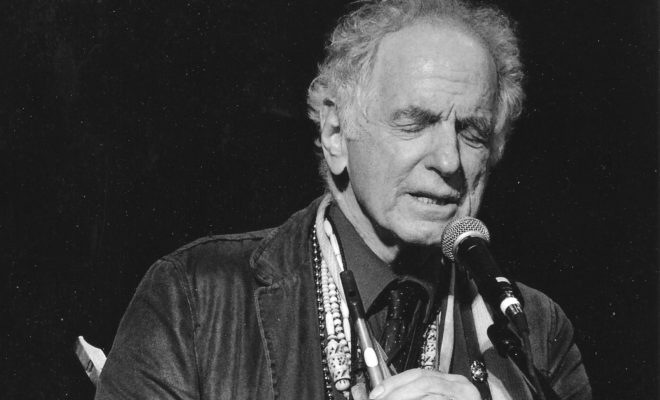

The Maestro of Collaboration: David Amram

By Gus Mollasis

When one encounters David Amram, they are forever transformed in every possible way. David Amram is a force of energy – boundless bits of that magical stuff Einstein postulated about – but even that does not quite capture this man’s true essence.

His essence, if dared to be theorized in a formula, is: one-part inclusion (I); one-part humility (H); one-part openness (O); and one very big part passion (P).

I + H+ O+ P = MC (Maestro Collaborator) who is no square.

Okay, so it’s not E = mc2. And it does sound more like a breakfast joint that he might frequent after a late-night gig, but you get the idea.

Its elements – inclusion, humility, openness, and passion – aptly describe the one and only David W. Amram.

I do know what the W in his name should stand for – WORLD, because his world is music and music is his world.

Now, 88 years young, this pied piper is still hopping all over this big and glorious planet bringing his brand of positivity and eclectic notes in his musician’s bag of instruments. He knows the one thing that all great artists know – that to create, to truly create, you must be open. It’s always a two-way street whenever you’re making art, whether on a film screen, during a jazz jam session, a late-night beat poetry reading or reciting some Shakespeare in the park. It’s all in the collaboration. From musician to musician and from player to listener.

Amram, who’s known affectionately as “Pops” by those who have played and worked with him, knows a lot about collaboration. If they gave out awards for it, he would have enough to fill Carnegie Hall. His treasured collaborations include a who’s who of artists such as: Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, Lionel Hampton, Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, Tito Puente, Betty Carter, Wynton Marsalis, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Pete Seeger, Odetta, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Joe Papp, Judy Collins, Patti Smith, Arthur Miller and Jack Kerouac.

Along the way he managed to compose a number of scores for major motion pictures including the iconic classics The Manchurian Candidate for director John Frankenheimer and Splendor in the Grass for Elia Kazan. He has also worked

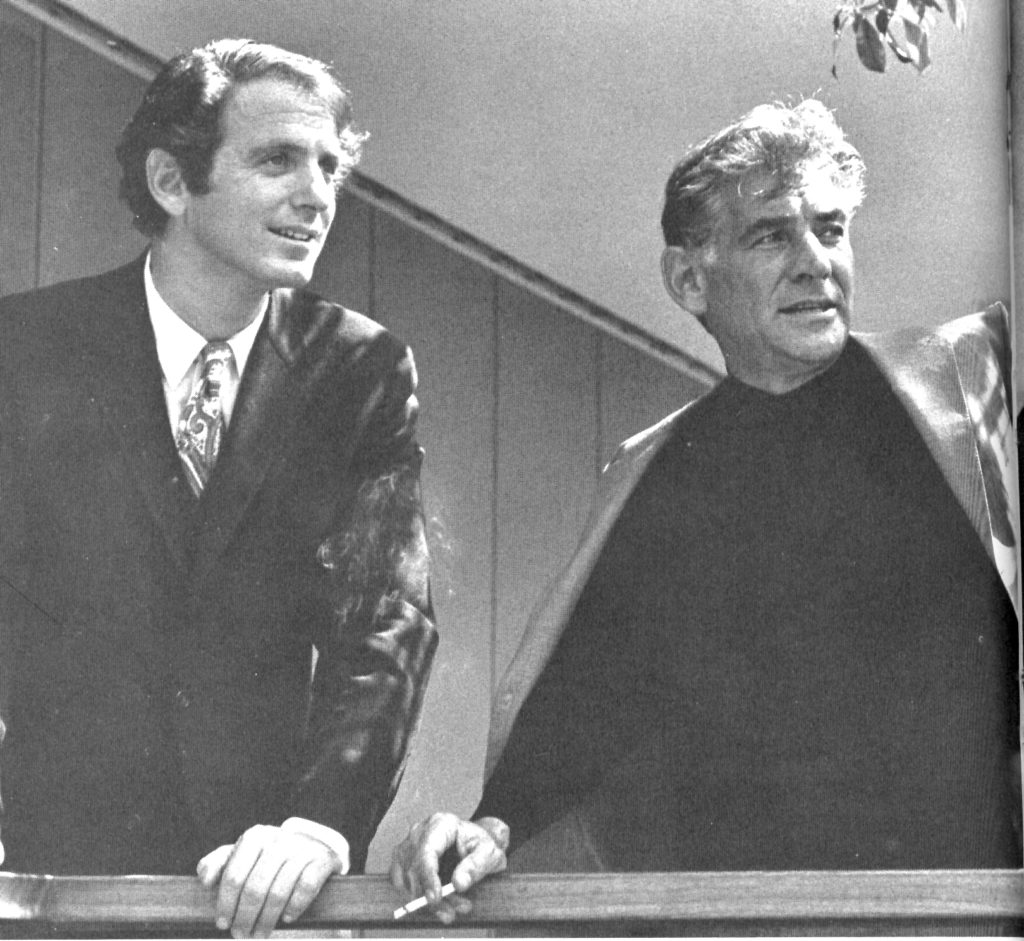

with the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Sir James Galway and Eugene Ormandy, to name a few. The list is too long to do it justice here.

Where he has played is as varied and eclectic. He was chosen by Leonard Bernstein to be the first Composer-in-Residence for the New York Philharmonic, has performed at Joe Papp’s NY Shakespeare Festival, and was there in the Village on that night in 1957 when the first ever “Jazz Poetry Reading” was performed with his friend Jack Kerouac. Like Jack, he still gladly finds himself on the road more often than not.

He’s been given numerous awards, most recently in 2017 when he received the Folk Alliance International’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

As a Jazz and Folk pioneer, this cool cat sings and scats, plays 35 instruments including his signature French Horn. He is also an acclaimed classical composer whose compositions incorporate his lifetime participation in the world of Jazz, Global Folk, Latin, Classical, Middle Eastern, and Native American music.

Over a seven-decade career, he’s been described as “a living legend, one of the great raconteurs of our time, and the real Zelig.”

The Boston Globe made this proclamation: “David Amram is the Renaissance Man of American Music.”

The Minneapolis Star and Tribune: “David Amram … a musical catalyst and leader on a par with Leonard Bernstein, Pete Seeger and Dizzy Gillespie.”

The Washington Post: “David Amram is one of the most versatile and skilled musicians America has ever produced.”

Wynton Marsalis says of Amram, “A Godsend to those who believe in the power of music to change lives and inspire.”

They are all right in their descriptions and interpretations of this man. But even these glowing tributes and compliments only scratch the surface of who he is and what he’s done in his life of music.

An author of numerous books, including his fourth book, David Amram: The Next 80 Years, will be published in 2020. The documentary film of the same name released in 2011 will be screened at the 2019 Sarasota Film Festival as part of a celebration of his life.

At 88, he’s still writing new music, and continuing to perform around the world as a guest conductor, soloist, multi-instrumentalist, band leader and narrator in five languages.

You can well imagine that as I was set to interview David Amram—who I call Pops because he’s my friend—I couldn’t wait to take a look at some poetic, jazzy and classical scenes from an interview of his life.

“Hello, Pops. How are you, my friend?”

Amram sends it back. “Okay, turn on the tape recorder till you can’t stand it anymore.”

Our jam session is underway.

What were the first notes you remember hearing and how was music first introduced to you?

For my 6th birthday my father bought me a bugle. I opened the box and saw the shiny instrument, and as I was about to pick it up, he picked it up and played it for 20 minutes himself. So, when I had children, I had to restrain myself from breaking into their presents. But I did enjoy watching him try to get a sound out of the bugle. Then he handed it to me and said, “You try it.” And I did, and I went, “Beep.” I got this big rush. Suddenly I was actually making a note of music. Since we had an old piano at my grandmother’s house, I started pounding away on that. Then we moved to our farm in Pass-a-Grille, Florida near St. Pete after I had finished the first grade around 1937. The public school there was doing a production of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker. They did the “Waltz of the Flowers” and I was a flower. I remember hearing his music and really liking it. Then I remember moving to our farm full time in Feasterville, PA, and in the 2nd grade I not only started playing the trumpet in the little bands that they had, but I would also listen to the old radiators on the farm make all kinds of crazy sounds when they were heating up. All those rhythms I could relate to hearing the great drummer Gene Krupa, great trumpet players like Harry James and Louie Armstrong, who you could hear on the radio. Somehow all these elements have stayed with me. I don’t know how the brain works, sort of like a hard drive, but it becomes part of your DNA.

Was there a moment of discovery when you knew that music would be that thing for you?

It was a constant process of evolution that still is going on for me at the age of 88. So instead of saying I’m going to retire on my laurels, I don’t even feel like I have any laurels. I’m interested every day in trying to learn and create new things and understand the old things that I thought I knew about, while being able to revisit them. It’s an endless process. Just like all major religions refer to the deity or deities as the great unknown. There is something out there that is bigger than all of us. And that’s a wonderful thing to realize, because then you can remain humble in knowing that you are just another tiny presence that’s here for a while and that there’s something bigger that was here before you and will be here after you’re gone. If you can get in touch with that while you’re here and share what you’ve learned with others to help them on their journey, whether its music or anything, then you’ve had a good life.

Today when you pick up and play an instrument, are you still that little boy who picked up that bugle as a child?

I’ve learned to get past my own disappointments with myself. I keep those private because no one wants to hear someone screaming the blues, who is able to do what they love to do and not have to have a day job. So, I’m blessed, I’m blessed with that. Also, you realize it’s important to encourage other people to do what they love to do. And secondly, you have to be grateful for having the chance to do it.

Was there a moment, a big break or the stars aligning, where you felt like there was divine intervention or inspiration to show you that you were on the right path?

When the great conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos, to whom I dedicated my first book, Vibrations, visited with my mother’s childhood friend who was Dimitri’s best friend, I was a teenager. He heard me practicing the horn, and he saw a piece I was trying to write. I think I was 14 and I heard him say to my mother, “He’s a good boy. He’s practicing on Sunday.”

Pops laughs and continues. I don’t think he knew I was Jewish and merely thought I was playing on a holy day. He was a devout Greek Orthodox who originally studied to be a priest. Of my piece he said, “You got something. You keep doing it. You have to learn to modulate.” I saw him ten years later when I was in the Seventh Army Symphony. He came over to help out our orchestra. He remembered and said, “Amram, have you learned to modulate?” I realized that not only was he nice to me when I was a kid, but he also wanted me to do better. That was a big thing for me.

And just as quickly the great collaborator is back with another story. With Pops there is always another story.

In 1951, Dizzy Gillespie came and crashed in my basement apartment with his whole band for the night in Washington D.C. The next morning, he said, “Get out your French Horn. Let’s play together. I want to hear you play.” And that was a big thrill.

The maestro breaks in with another tune.

The next year I met Charlie Parker, and he spent the whole night encouraging me to write symphony music to reflect my interest, way back then in what they called jazz of world music. He told me to find a way to put all those things together and to keep playing jazz on the French Horn which, just like trying to be a symphony composer, was considered to be impossible.

He comes back with more.

Finally, when Leonard Bernstein chose me as the first ever Composer-in-Residence at the New York Philharmonic, he explained to me what I should try to do with my life. Not only to please myself, but to add to the repertoire and to be an ambassador of music for young people.

Playing with Floyd Red Crow Westerman, the great Native American singer, for 40 years and at Farm Aid with Willie Nelson for the last 30 years, along with Pete Seeger at various times, showed me the treasures of indigenous American music. In all forms they have endorsed traditional Folk, Jazz, Blues, Cajun and Native American music and helped teach me not to forget the beauty of each and every one, while appreciating the preciousness of everyone’s heritage that helped create these different forms and languages of music.

Your renowned ability to collaborate in various musical genres and with varied musicians, is that something that everyone can do?

I’ve been to countries from Panama to Cuba and recently Germany where I’ve found that because of the Internet, younger musicians have access to everything. If you’re patient enough, you have the ability to find those needles in a haystack and the treasures of music from all over the world with instruction for free from masters who want to pass that on in various forms. Kids will ask me how I learned to do so many things. I tell them that my YouTube was being a full-time scholarship student in the “University of Hang-out-ology” where we hung around people at three in the morning who asked us to come and play with them. Everyone has their financial responsibilities they have to meet, pay the rent, dental, and eats, but above and beyond that, even in your off hours, if you do other things to pay those bills, you can still be an artist and an inquisitive person and get educated in the U of Hang-out-ology. There’s no tuition for that. All you need is an open mind and heart. And if you share what you’ve learned with others, people can see in your face whether you’re with them in a humble, studious way, or just another big rip-off artist. People can tell the difference.

You’ve been described as having a profound influence on world music. How would you describe yourself as a musician?

I would say that world music has had a profound influence on me. I’m basically a composer, and everything that I’ve done and still do reflects when I’m sitting in that room with a blank sheet of paper trying to put something down on that paper. Hoping it is something that will speak to the musicians so that they will play it and it can make them feel something in themselves like a sense of wonder that they haven’t be there before. That in turn will speak to those who listen, because if you can stimulate creativity in people who are performing it by accurately notating exactly what it should be, that’s important. There’s no way that you can do that if you haven’t experienced it yourself in some way. I think that all art that lasts is storytelling, picture painting and conversation with others.

Are there some special nights you performed that stand out in your mind after all these years and all the performances?

Some of my highlights were playing in Paris in 1955 the night that we got the news that Charlie Parker had died. When I played The Way You Look Tonight, I suddenly got carried into another level I never dreamed could happen. Many years later in January 2019, I conducted a wonderful symphony orchestra in my Elegy for Violin and Orchestra at Carnegie Hall with Elmira Darvarova playing. Suddenly I flashed back to when I was conducting from earlier days and thought of some mentors and people I admired. I could picture Stravinsky there, and Mitropoulos and Leonard Bernstein watching me, and knowing that that’s where Tchaikovsky conducted the very first time when they were opening the hall. I remembered when I was a kid and seeing those movies of New York and Carnegie Hall thinking that I could never have dreamed that this would happen to me. And then two days later, I was playing in a little folk place in Saratoga where I met the mother of my three children 42 years earlier. I thought it’s so amazing what life can provide. Experiences stay in your mind forever and you realize that you’re supposed to bring those highlights with you wherever you go. I also flashed back to the night Charles Mingus told me at the Café Bohemian, my very first night playing professionally in New York, that no matter how ratty the joint, every night is Carnegie Hall. Here it is 64 years later, and I am here at Carnegie Hall conducting a tremendous orchestra.

Pops, please finish the following sentences:

When I’m playing music…

I am in the moment.

Music to me is…

The food of love, just as Shakespeare said. Can’t beat Willie the Shake.

The greatest joy in playing is…

Being able to honor who you are playing with, whose music it is, and being part of the whole.

Is there a quote that you live by?

There are never too many sunsets and never enough beauty.

Of your many compositions, do you have a favorite?

My Triple Concerto for Woodwind, Brass and Jazz Quintets & Orchestra and “This Land is Your Land” (Symphonic Variations on a Song by Woody Guthrie).

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when I mention the following people:

• Dizzy Gillespie: Warm and Inclusive

• Dimitri Mitropoulos: Spiritual Genius

• Elia Kazan: Totally in the Moment

• Leonard Bernstein: Total Genius

• Willie Nelson: Warm, Embracing and Brilliant

• Jack Kerouac: Soulful, True, Storyteller

• Charles Mingus: Spontaneous Composer

• Pete Seeger: World Ambassador of all Sincere Music

• Odetta: Keeper of the Flame

• Bob Dylan: Amazing Poet

• Patti Smith: Brilliant Storyteller

• Charlie Parker: Architect of New Beauty

• Joe Papp: One hundred percent committed

• Sir James Galway: Greatest Virtuoso

Please share your experience working in the movies and on the iconic films The Manchurian Candidate and Splendor in the Grass.

I am a composer who occasionally writes scores for films that I love, where I can have free reign to do the best music I possibly can. My scores for The Manchurian Candidate and Splendor in the Grass I orchestrated and wrote every note myself, conducted it, chose the musicians who played, and I put as much loving care into that as I have done in writing my operas, symphonies, concertos and everything else. I loved every second of it and I’m especially proud of those two films and the music that I wrote, and I’m proud of all the other music I’ve done since then. Recently I’ve worked with Barbara Kopple, a two-time Oscar winner, who I’ve known for 30 years before collaborating with her. When I’m with her, I feel the same way I felt when I was with Kazan and Frankenheimer. She’s a real artist who loves every second of what she does.”

Do you have a favorite place to jam?

My favorite place to jam over the last 14 years has been Cornelia Street Café. And they just closed down after 41 years because the rents were so staggering. I love playing Farm Aid every year. Anyplace that I am, anywhere in the world, I try to bring Greenwich Village and Carnegie Hall, Farm Aid and the New York Philharmonic to wherever I am. So, I never feel like I’m in a small or unfamiliar place. I realize that each time I’m doing it, it’s the first and the last time, so you better do the very best possible.

Tell me about that first and last time you did that Beat poetry reading with your friend, the great Jack Kerouac.

The very first time was at a “bring your own bottle party” before On the Road was published and nobody was listening. He handed me a piece of paper then took it back and then I played with him. I was stunned by the feeling I got of doing that with him. I didn’t even know exactly what we were doing but I felt like it was really something. The last one publically was at Brooklyn College and by that time On the Road had come out and Jazz poetry, we called it music poetry, suddenly became fashionable. Six months later it died a natural death as people would scream into the microphone as loud as possible and the band would play “I Got Rhythm” faster than it had ever been played before. And nobody listened to anybody. It’s nobody’s fault. It happens with all things in fashion. Fortunately, the Doors came along, as did the lost poets, hip hoppers and the freestylers who are phenomenal in a whole different way. And now, when I do my readings of Kerouac, people are shocked. I get actors and people who love his work who don’t have an obligation to be a screaming psychotic. You really don’t even need musical accompaniment during poetry readings – the poetry is the music.

What keeps you going?

I think it’s that when I was a little kid, and I used to hear that train go by the railroad station which was about two or three miles from our farm. I could hear that engine on the express train to New York called The Crusader. Every time it passed, I remember hearing that whistle and thinking boy, maybe someday if I’m lucky, I can go to the fabled place called New York and see a band or orchestra or play with a band or something like that if I can’t be a farmer. It was such a wonder. I still have that. I live in Beacon, so when I hear a train whistle I’m reminded of that kid. And every time I think maybe it’s time to pack it in, there’s someplace I really like to be. I’m so excited every time I leave the house to go and do anything. And when I’m home composing, my biggest problem is knowing when to stop, which is usually when the sun comes up.

How does it feel to be honored by the Sarasota Film Festival with a Lifetime Achievement Award?

It’s a special honor because I went to the first grade in Pass-a-Grille, Florida. Secondly, because Sarasota has been an oasis and beautiful place for as long as I can remember. We would visit when I was child and always remember it so fondly. Finally, the Sarasota Film Festival has always celebrated excellence in film rather than just being about networking. It’s a real honor and I’m grateful. And of course, I get to see you and Mark Reese, who I collaborated with on your film, Jack Kerouac Slept Here.

Many years from after all the concerts have been played and the music has been composed, how do you want to be remembered?

I would say as a composer who tried to share his blessings.

David Amram will be honored at the 2019 Sarasota Film Festival with a Lifetime Achievement Award which takes place April 5 – April 14. For more information, visit SarasotaFilmFestival.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login