Literature

Literary Scene: A Conversation with Local Author David Adams Cleveland

By Ryan G. Van Cleave | April 2022

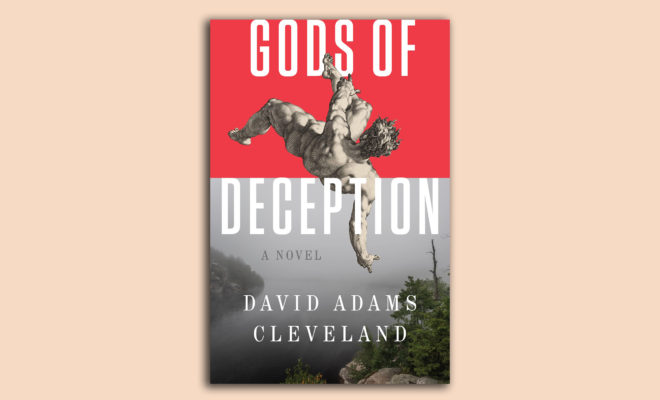

It’s not often that art historians are able to transform a deep love for history into engaging novels, but since 2013, that’s exactly what David Adams Cleveland has done. His latest effort, Gods of Deception, imagines the final days of a judge who once presided over the 1950 Cold War trial of real-world Soviet spy Alger Hiss. I chatted with David, a part-time Siesta Key resident, to learn a bit more about this book and his writing career.

What’s the casual dinner party answer to “Oh, you just had a novel published? What’s it about?”

Often this question is posed with an attitude attached (“if you’ve had a novel published and I didn’t already know about it, much less haven’t heard of you, then you can’t be much of a novelist”). One is then faced with the prospect of trying to temper such skepticism with the elevator pitch about the plot, or to casually wave the whole thing off, remarking: I write literary novels that only a chosen few reviewers and intelligent readers bother with.

It seems we live in a culture (the art world is not dissimilar) where fame is the coin of the realm. Or as an astute reader of mine once offered: If you only wrote shorter books, you’d be famous by now. To which I mention the refrain I’ve heard a hundred times at signings from Maine to Florida, at tiny indies or sprawling Barnes & Nobles: “Oh golly, such a long novel—but you know: (sotto voce) If I love a book, I never want it to end.”

What’s the story behind the story of Gods of Deception?

Since I first became aware of the Hiss spy case (“the trial of the century”) when I was studying history in college, I was always intrigued—how on earth could half the nation believe that Hiss was a spy after his conviction for perjury in 1950, and the other half believe he’d been framed by Hoover and the FBI and enemies of the New Deal led by his accuser Whittaker Chambers? One was reminded of the way the Dreyfus Affair divided France into warring camps for a generation, or how, more recently, the OJ trial split America.

I remembered as a kid my parents watching heated arguments on William Buckley’s Firing Line between supporters of Hiss and partisans of his spy-handler, Whittaker Chambers. What exactly was at stake? Once the ultimate verdict began to filter in during the early 2000s with the declassification of Soviet cable traffic from the WWII era (Venona), and access to KGB files during the Boris Yeltsin presidency of Russia (after the fall of the Berlin Wall), and it was confirmed that Alger Hiss had indeed been a spy—an agent of influence sitting at Roosevelt’s right hand at Yalta, I began to wonder about the lawyers who had been on Hiss’s defense team. Hadn’t they suspected something fishy about their client’s earnest denials of wrongdoing? Did they know or suspect the truth all along or were they, too, confounded by Hiss’s golden-boy stature as a member of the Eastern establishment? Like good defense lawyers they took any doubts to their graves.

I found myself inspired to develop one of my main characters in Gods of Deception, Judge Edward Dimock—a member of the Hiss defense team—who at 95 with failing memory is intent on finishing his long-delayed memoir about the Hiss trial. He summons his grandson, a Princeton astrophysicist, to his fabled Catskill retreat, Hermitage, to help uncover the truth about Alger Hiss. And so, through the Judge’s memoir and the sleuthing of his grandson, George Altmann, the harrowing inner workings of the Alger Hiss spy trail are revealed, along with a series of unsolved deaths surrounding the case.

Over the course of writing this novel, what surprised you the most?

I began my research for the book thinking that Alger Hiss was a spy for Soviet military intelligence back in the late 1930s, only to realize that the real damage he did was as an agent of influence in the highest reaches of the State Department during WWII and its aftermath. We now know that Hiss, a Soviet asset, sat at Roosevelt’s right hand at Yalta, and each morning was debriefed by his handler about the American and allied negotiating position vis-a-vis the post-war disposition of Eastern Europe and the Far East. On the way back from Yalta, stopping in Moscow with elements of the American delegation, Hiss was taken aside by the head of Soviet intelligence, and in a secret ceremony presented with the Order of the Red Star. Hiss was just one of over 500 Soviet agents embedded in the US government—including Roosevelt’s White House—and related war industries.

How do your various identities feed each other?

Fiction writing and art history may seem like very different avocations, but I find that they neatly complement each other. In my novels, I try my best to set scenes with the palette of a painter, while in my art history, I try to tell compelling stories about artists—the challenges and inspirations that shaped their art. I think the best novels not only provide telling details about the setting (character and plot)—their pages express a certain tone or atmosphere—something the reader feels in her bones—an emotional quality that stays with the reader long after the plot, or even the characters, have been forgotten.

What’s next for you?

I’m on the third draft of my fifth novel (working title, Reunions) about four women at their 40th reunion where they run into a graduating senior who’s the son and spitting image of a much-beloved classmate, who knows more about their past lives as students (and their torrid affairs) than any kid should know. It’s less than 400 pages, so my readers will be disappointed in its brevity.

Abbeville Press, who publishes my art history, also has me on tap to do a shorter version of my American Tonalism book, a book that will include tips on collecting, connoisseurship, and how to purchase art you will keep enjoying for the rest of your life.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login